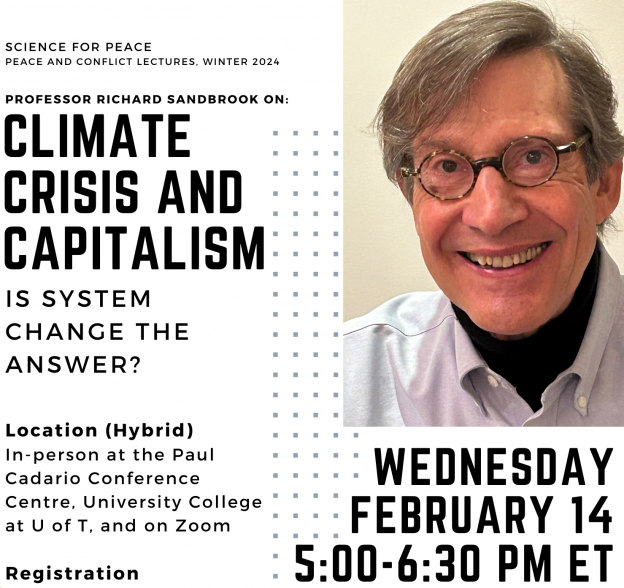

This 55-minute lecture assesses approaches for surmounting the accelerating climate crisis. i focus on the desirability, viability, and potential feasibility of these approaches.

The argument is simple.

This 55-minute lecture assesses approaches for surmounting the accelerating climate crisis. i focus on the desirability, viability, and potential feasibility of these approaches.

The argument is simple.

Richard Sandbrook and Arnd Jurgensen

Richard Sandbrook is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at University of Toronto. Arnd Jurgensen lectures in international relations at University of Toronto. Both are executive members of Science for Peace, whose board members debated the issues discussed here.

One prevalent explanation of the war in Ukraine pins the blame on Russia; the other, which has little institutional backing in the West, but far more outside the West, blames NATO. Proponents of each view largely ignore the opposing interpretation. Both sides agree the war is illegal under international law, but there the agreement ends. For those who blame NATO, their declaration of the illegality of the invasion is largely a formality because, from their viewpoint, NATO provoked Russia to invade Ukraine. For those who blame Russia, the invasion is not only illegal under international law but also a travesty of “unprovoked” aggression.

Yet neither side is blameless in this terrible war. To acknowledge that fact is an important step to envisioning a just and lasting settlement.

Conflicting Viewpoints

Consider first the anti-NATO interpretation. They see the existence of NATO as a problem. It is not hard to understand why.

NATO portrays itself as a strictly defensive club of democracies that share basic values and is compelled to admit other North Atlantic states that ascribe to them. Yet all military alliances need an enemy to justify their existence. The external threat that gave rise to the alliance – the USSR and the Warsaw Pact – disappeared in 1991, as should have NATO. NATO lost an opportunity in the 1990s, when the Soviet Union expired, to build bridges to Russia. NATO’s expansion to the borders of Russia and its willingness to arm and contemplate future membership of Ukraine and Georgia in NATO were provocations. Russia considers Ukraine as within its cultural, economic and political sphere of influence. Russia, of course, does not have a “right” to a sphere of influence, any more than does the United States in its own neighbourhood. But spheres of influence have always gone along with Great-Power status, whether we think it justified or not, Russia would inevitably feel threatened if NATO and the European Union incorporated Ukraine, with its close historical links and proximity to Russia, within its “Western” sphere.

However, from the opposing viewpoint, Russia for its part has made aggressive moves that frightened its neighbours. Eastern European states were not forced to join NATO; they applied for membership because, from historical experience, they mistrusted Russia. Within historical memory are Stain’s partnership with Hitler, 1939-1941, and the postwar imposition of Communist regimes in Eastern and Central Europe. In recent years, the intervention of Russian forces in Georgia and Moldova and covert use of Russian troops in Ukraine’s Donbass in support of separatists have rekindled the fears of former Soviet client states. Moreover, the brutality of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has stirred further resentment and fear in neighbouring states, such as Finland and Sweden (who are now joining NATO).

In short, neither side is without some responsibility for this dreadful and unnecessary war.

Blame and Conflict Resolution

Apportionment of blame for the current conflict, however, is currently a distraction from the need to bring the war to an end. Such discussions must at some point take place to determine issues of reparations in the context of negotiations, but they must not derail attempts to engineer a ceasefire. The same is true concerning international law. Clearly the invasion of Ukrainian territory was a violation of the sovereignty of a recognized state, and it is, as such, a crime of aggression (which, as Justice Robert Jackson of the Nuremberg tribunals explained, is the highest crime under international law as it entails all the evils war necessarily brings with it). The United Nations Charter also recognizes the right to self-determination of nations, which implies the right of the Donbass and Crimea to declare their independence from Ukraine (a principle that NATO endorsed with its armed intervention in Kosovo).

These principles, again, raise issues that must ultimately be resolved; but disagreements on these issues must not stand in the way of ending the killing and destruction in Ukraine. Other oft-cited issues are also irrelevant to a settlement, including corruption in Ukraine or autocracy in Russia. These issues are relevant for the people of Ukraine and Russia, as are the personality traits of their leaders, but not to the need to end this war.

At present, neither side is inclined toward negotiations and a cessation of hostilities. Negotiations will have to take place sometime – unless Russia achieves total victory (and it’s not clear what that would look like), or Ukraine does (which is highly unlikely, given Russia’s much larger pool of recruits for the armed forces and actual and potential firepower). A Ukrainian victory would also risk igniting a nuclear war. However, if the upcoming Ukraine counter-offensive ends in stalemate, both sides may judge that their interests are best served by negotiating a peace settlement.

Reconciling Conflicting Principles

What might be the terms of a settlement that is (barely) acceptable to both sides? If we accept the shared responsibility for this war, each side will have to compromise. A resolution demands that two principles of international law be recognized: the inadmissibility of aggression leading to land-grabs, and the right of peoples to self-determination, if a clear majority opts for this outcome. Boundaries will have to be drawn that reflect the preferences of those who live within them. Unless the borders reflect such preferences, they will remain unstable and a future source of conflict.

There is no prospect of the ongoing destruction moving in the direction of resolving this dimension of the conflict. Instead, a UN monitored process of consultation and popular referenda would be most likely to produce such an outcome. To have legitimacy, the vote must include those who have fled their homes as well as those who have stayed. These boundaries will also have to be secure. In the long term, that can only happen through neutrality for Ukraine, border guarantees, and the creation of a new security architecture including Russia (perhaps including the withdrawal of long-range missiles from Poland).

Recognizing the Dangers, Forging Peace

The need for action is acute. If Ukraine should strike into Russian-held territory, using western weapons and intelligence, the possibility of escalation and nuclear war rises ever higher. Ukraine has the right to defend itself, but can Ukraine ever defeat a nuclear power with a much larger armed forces, even with weapons from the West?

To let this conflict fester poses an unacceptable risk to the survival of humanity. The only sane position is peace negotiations now – based on the notion of shared responsibility for this war.

“Disinformation” undoubtedly exists as a form of warfare in this contentious age of artificial intelligence. But how do we know disinformation when we come across it? The obvious danger is that officials and activists will dismiss strongly opposing views as disinformation, not to be taken seriously, or, at worse as potential sedition to be investigated.

An article in the March 30th (2023) Globe & Mail (Toronto) exemplifies this danger. Entitled “Pro-Kremlin Twitter Accounts ‘Weaponizing’ Users to Erode Canadians’ Support for Ukraine, Study Finds,” the article suggests that 200,000 Twitter accounts have been established in Canada that propagate the Kremlin’s line on Ukraine. The purported aim of this campaign is to undermine Canadian support for the Ukrainian government. Three centres, two at universities, conducted the study, which was supported financially by the Canadian and United States governments. Allegedly, the disinformation campaign succeeded to the extent that both “far right” and “far left” Twitter accounts extensively “shared’” the disinformation on their own networks.

What is the evidence for the impact of this alleged disinformation campaign? The article notes that 36 per cent of respondents in a recent Canadian survey believed that NATO was responsible for the war, or were unsure. Clearly, the writers of the report (entitled “Enemy of My Enemy”) believe that NATO holds no responsibility for the war. To uphold the opposite view is tantamount to disinformation or being uninformed.

And yet the idea that NATO provoked, or at least did not act to prevent, the war is not far-fetched or merely Russian propaganda. Neither side is blameless. NATO portrays itself as a strictly defensive club of democracies that share basic values and are compelled to admit other states that ascribe to them. Yet all military alliances need an enemy to justify their existence. The external threat that gave rise to the alliance – the USSR and the Warsaw Pact – disappeared in 1991, as should have NATO. NATO lost an opportunity in the 1990s, when the Soviet Union expired, to build bridges to Russia. NATO’s expansion to the borders of Russia and its willingness to arm and contemplate future membership of Ukraine in NATO were provocations. Russia considers Ukraine as within its cultural and political sphere of influence; Russian fears of NATO’s intentions are thus not unreasonable. However, Russia for its part has made aggressive moves in Georgia, Moldova and elsewhere that have rekindled the fears of former client states of the Soviet Union. The brutality of its invasion of Ukraine is unjustifiable. Neither side is without some responsibility for this dreadful and unnecessary war.

Consequently, debates are raging in academic and activist circles over apportioning responsibility for the conflict. Moreover, the left (contrary to the report’s view of a homogeneity of views) is split in its interpretation of the war, leading to many acrimonious exchanges.

It might be argued that the report itself is an example of disinformation. The article that describes the report provides no criteria for distinguishing the Twitter accounts engaged in disinformation, other than that the views they propound cohere with themes of the Russian narrative. The report veers toward the Red Scare techniques of the Cold war. But let’s be clear: you can advocate the view that NATO shares part of the blame for the war without in any way being part of Russia’s disinformation campaign.

Having said this much, I must also state that disinformation does exist. I know because I have debated with a bot. On a Canada-wide network of peace activists, I have been critical of those who jump to the conclusion that the war in Ukraine is a NATO war. Bots entered the intellectual fray, but one of them was very poorly programmed. It acted like a parody of a bot: in one message, claiming to speak on behalf of the ostensibly Western-oppressed “Third World” (this archaic term itself being a tip-off); in the next as an outraged representative of the people of the Donbass, allegedly brutalized by the “Nazi” government in Kyiv. It was over the top in the most extreme version of Russian disinformation and bombast. It was a stupid bot. Bots like this give artificial intelligence a bad name.

The global situation is complex. Yes, there is disinformation undertaken by Russian agencies. But let us be careful not to equate disinformation with any ideas that conflict with the dominant Western narrative. If we allow that to happen, we will find ourselves returning to the era of US Senator Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s, with his “unamerican activities committee” rooting out fellow travelers of the Communists.

Those in Canada who dissent on the war are not “unCanadian” and rarely are they engaging in disinformation. We may disagree with their positions. Yet that disagreement is a healthy aspect of our democracy. And yes, disinformation and bots are real; but some of the bots are laughably stupid.

Humanity faces the gravest crisis in our short history. Our governmental leaders are unwilling or unable to grapple effectively with two looming catastrophes: escalating climatic disasters and growing arsenals of increasingly deadlier nuclear arsenals, combined with rising tensions among nuclear powers. Authoritarian tendencies throughout the world make matters worse, as far-right deniers and conspiracy theorists rise to the fore.

Grappling effectively with these problems certainly benefit from scientific analyses of why the problems exist and of what might serve as technically sufficient policy or programmatic solutions. But what is often lacking is an answer to the crucial how question: How, realistically, will the solution be implemented? By whom? With what coalition, ideology and set of tactics? Without rough answers to the political question, we are engaging merely in dreaming about desirable worlds.

The dangers are now so acute that only drastic action can avert catastrophe. Even holding global warming to a disastrous 2 degrees Celsius this century will require emergency action akin to mobilization for war. Preventing an accidental or intentional exchange of nuclear weapons requires a transformation of the dominant, military and nationally based conception of “national security.” With the proliferation of both nuclear-armed countries and the number and destructiveness of nuclear weapons, we are all becoming increasingly insecure. Avoiding the real possibility of civilizational collapse means rocking the boat, disrupting the status quo.

The challenges are urgent and complex; who will lead the way in confronting them?

You might think that such emergencies would galvanize universities and colleges to prepare their students and the public to understand and transform this dangerous world. But universities are reluctant to take on this role. Of course, we can name commendable exceptions and scattered units within universities dedicated to environmental and peace and conflict studies. Dependent on financial contributions from governments, corporations and rich individuals, universities and colleges do not confront power structures and ingrained beliefs that buttress a dysfunctional system. This reluctance places a burden on independent think tanks in civil society.

Science for Peace, the Canadian voluntary organization to which I belong, is similar with independent thank tanks elsewhere striving to apply scientific knowledge to resolve crises. The value of a think tank lies in taking the longer view. Although it may engage in campaigns on immediate conflicts, its vocation lies in presenting a comprehensive and integrated vision of what should and can be done to remedy wicked problems.

Canada’s Fraser Institute, like similar right-wing think tanks elsewhere such as the UK’s Institute of Economic Affairs and the US’s Cato Institute, is effective for three reasons. All its research and public education not only focus on promoting free-market solutions, but also reflects the vision. ingrained individualism, and paradigmatic policies of neoliberalism. Obviously, the massive funding that this viewpoint garners from corporations and the rick augments the Institute’s influence.

Science for Peace and other NGOs think tanks will never match the Fraser Institute (or the other two) in highly paid consultants, salaried professional managers, access to key policy-makers, and slick presentations. However, the positive side of our reliance on committed volunteers and shoe-string budgets is independence from both government and corporations. We can voice the uncomfortable truths about what needs to be done, and how.

We “can,” but do we?

Not as well as we might like. If we are taking the longer view – if that is our goal – then what is the coherent message? As for Science for Peace, our “Peace/Ecological Manifesto” does integrate our thinking by linking the ecological crisis to the nuclear/militarist challenge and by offering a theoretical alternative to the current order, namely, “human security”. We do not propose, however, a plausible pathway to the new order. And our webinars, lectures, statements, petitions, and articles address disparate, albeit important, topics. We have elaborated the severity of the nuclear and climate crises, though too much emphasis on the scope of the emergency can induce paralysis rather than action. We have probed the nature and origins of instances of human suffering, such as the war in Ukraine. Lately, we have focused on the promise and tactics of nonviolent resistance, especially in the context of authoritarian tendencies. And we have taken principled stands in petitions and statements on a range of peace and climate issues. Principles are important; however, sometimes the message is received by those already converted. In short, our offerings are pertinent, though not informed by a coherent strategy. Science for Peace is typical in this respect.

Independent think tanks can be more effective if they have a consistent and reasonable message, which they relay through all means of influence. Yes, we need a luminescent vision of a peaceful and sustainable world. However, the harder part is imagining and forging the feasible pathways for surmounting our predicament. Our research and education should reflect an integrated perspective.

A “pathway” is akin to a strategy in the broad sense. A strategy involves answering three questions:

In general, the “why” and “what” questions are easier to answer than the “how” question. The conservative think tanks have answers to all three questions. Independent think tanks emphasize the “what,” with some attention to “why.” Without answering the last question, however, one is engaging only in dreaming. We have enough scientific knowledge to know what to do, but we don’t do it. We need to focus on how what needs to be done, gets done.

What is the strategy? It doesn’t need to be spelled out in detail; we don’t have all the answers.

We are in the business of helping to avert two looming catastrophes. My view is that we should be explicit about the need for structural/system change, though without mentioning either capitalism or socialism (as both terms are vague and are weapons used in ideological/political warfare). We might use the more neutral term ’market system’: is there any doubt that the market system is obsolete when it is rapidly undermining the ecological basis of all life? We can oppose the market system, which destructively treats nature and labour as commodities, while still accepting the importance of markets in real commodities in adjusting supply to demand. “Human security” and “Postgrowth” are other positive terms to employ.

Too often analysts and activists frame the macro-strategic choices as revolutionary or reformist change. That is a false dichotomy. For one thing, system change does not necessarily mean the end of capitalism. Yes, we cannot continue with endless growth, especially in the rich countries. However, those who propose movement toward a steady-state economy, an idea associated with ecological economist Herman Daly, or “postgrowth,” implicitly or explicitly contend that this transition can be made within capitalism. Through-puts of energy and resources remain constant, but competition, entrepreneurship and innovation continue to produce goods more efficiently and invent new products. A steady-state economy or postgrowth is our future.

For another thing, reformism breaks down into two categories: policy reforms that can be implemented within the existing power structures and economic system (usually the position of policy analysis as practised at universities), and radical reforms that will become feasible under foreseeable conditions (that is, human agency can shape the sociopolitical conditions). The last is implicitly, for example, what climate scientists are tending toward in their opaque reports for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Scientists claim that “holistic and transformative change” is required to hold global warming to under 2 degrees Celsius. Those changes could only come about via a shift in power structures. In short, the difference between those arguing for system change and those arguing for policy changes is, in some cases, not as deep as it may appear.

What we should aim for is radical reformism with respect both to global warming and to the nuclear threat arising from the international balance of power/terror system. Reforms within neoliberalism are unlikely to resolve the challenges; revolutionary change is not only highly uncertain, but also costly in human suffering. Radical reformism, linked to nonviolent civil resistance, is the only feasible and humane approach in averting catastrophes.

This advocacy of radical reformism is becoming mainstream. On the issue of postgrowth, for example, consider this project funded by the European Research Council with a budget of €10 million. On the issue of dealing with the threat of nuclear annihilation, refer to this appeal, which is supported by many prominent scholars and activists globally. The manifesto calls for the establishment of a new international order, based on a massive global mobilization of civil societies.

The conclusion is simple. We are in a dangerous era in which boldness is essential in dealing with looming catastrophes. For Science for Peace and other peace and climate organizations to act effectively, we must offer an integrated, reasonable, comprehensive, and radical message.

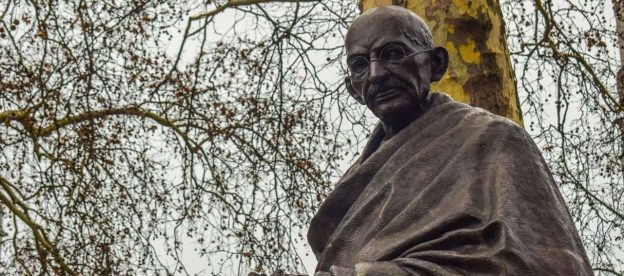

However, in practice, principled proponents, such as Gandhi and Martin Luther King, proved to be adept at pragmatically using nonviolent methods, Equally, some pragmatists, in their hearts, are pacifists as well as hard-headed realists.

Unarmed civilians employ coordinated and unconventional methods to deter or defend against usurpers and foreign aggressors or to overturn injustices, though without causing or threatening bodily harm to their opponents. Examples of nonviolent methods include demonstrations, protests, strikes, stay-at-homes, boycotts, street theatre, derision of authorities, rebellious graffiti and other communications, shunning of collaborators, building alternative institutions, and many more.

It is not passive, but active, demanding coordinated and unconventional struggle. Far from evincing weakness, NVR demands immense courage of resisters, who are aware their resistance may lead to injury, imprisonment, torture, or even death. NVR is thus not for the weak-hearted. It is a strategy only for those with the determination to persist in the face of repression.

NVR movements succeed by building up a large and diverse following of activists, winning over passive supporters, and precipitating demoralization and defections among the pillars of the established order (the police, army, bureaucrats, insiders).

Erica Chenoworth, who has undertaken path-breaking research, discovers that, of the 627 revolutionary campaigns waged worldwide between 1900 and 2019, more than half of the nonviolent campaigns succeeded in achieving their goals, whereas only about a quarter of the violent ones succeeded. Nonviolent struggles are twice as effective as violent struggles. Yet the influence of the military-industrial complex, the widespread glorification of violence in popular culture and the equating of masculinity with domination obscure the superiority of nonviolence as a political stratagem.

6. The leverage of NVR stems from the dependence of rulers on the consent of significant sectors of the population (Gene Sharp).

Rulers cannot rule if bureaucrats obstruct, armed forces and police hold back, people shirk work and ignore laws and regulations, and foreign powers desert. Rulers do not need the support of entire populations; the Nazis could destroy Jews, Roma, the mentally and physically disabled, socialists and union leaders, so long as the ethnic Germans acquiesced to their rule. Hence, the task of nonviolent resisters is fourfold: -to build a large and diverse movement -to attract the loyalty of passive supporters -to encourage the defection of pillars of the regime -to build support in the international community.

Civilian-based defence, in the words of Gene Sharp in his book of that name (1990) is “a policy [whereby] the whole population and the society’s institutions become the fighting forces. Their weaponry consists of a vast variety of forms of psychological, economic, social, and political resistance and counter-attack. This policy aims to deter attacks and to defend against them by preparations to make the society unrulable by would-be tyrants and aggressors. The trained population and the society’s institutions would be prepared to deny attackers their objectives and to make consolidation of political control impossible. These aims would be achieved by applying massive and selective noncooperation and defiance. In addition, where possible, the defending country would aim to create maximum international problems for the attackers and to subvert the reliability of their troops and functionaries.” History holds many examples of civilian defence, including in Denmark and Norway during Nazi occupation and in Czechoslovakia following the 1968 “Prague Spring,” when a Warsaw Pact army sought to reimpose rigid Soviet-style Communism.

Although nonviolent campaigns worldwide reached unprecedented numbers prior to the 2020 pandemic, their success rate fell. Erica Chenoworth in her 2021 book Civil Resistance provides the statistics. (However, nonviolent resistance remained more effective than violent campaigns.) Chenoworth also offers some tentative reasons for this comparative decline. She highlights “smart repression” by governments and strategic errors on the part of resistance movements. Each is a major subject, and each demands attention if NVR is not to repeat the errors of the past. Restrictions accompanying the pandemic (2020-2022) dampened NVR by rendering mass gatherings illegal and/or dangerous.

Nonviolent movements’ strength depends on maintaining unity among a diverse following, sustaining nonviolent discipline, and demonstrating versatility in nonviolent methods. Determined rulers will undermine the movement’s unity, provoke violent responses, and neutralize the leadership. Digital means of communication have assisted NVR movements in mobilizing large numbers of protesters and in spreading their messages via social media. But there is a dark side to digital technology. It allows governments to enhance surveillance of dissidents, identify leaders, and sow discord through misinformation campaigns. The effectiveness of the next phase of NVR depends both on neutralizing smart resistance and returning to the fundamentals of nonviolence: organization, training, nonviolent discipline, and the versatile use of the full panoply of nonviolent techniques

The relationship between violent and nonviolent action is not as clear-cut as it may at first appear.

In principle, as nonviolence guru Gene Sharp repeatedly reminds us, violence must not be combined with nonviolent action. Why? For one thing, violence will undermine the legitimacy and moral high ground enjoyed by nonviolent resisters. Why is this legitimacy so important? Because of its effect in undermining the morale of the violent attackers, creating dissension among supporters of the invaders/usurpers, and building international support to sanction the aggressors/usurpers of power. Conversely, violence creates fear that not only scares off potential supporters or resistance, but also motivates the oppressor’s police and armed forces to fight back more determinedly. Thus, nonviolent discipline is a key to success, claims Sharp with few dissenting.

In reality, however, violence has played a larger role in effective nonviolent movements than is often acknowledged.

Note first that Sharp encompasses within nonviolence those acts designed to destroy strategically important property and infrastructure. He does add one important proviso: acts of sabotage must not kill or maim civilians or soldiers. Yes, civilian defenders can destroy equipment, files, computers, even bridges and tunnels. But be cautious, Sharp warns: this tactic is risky. If property destruction leads to inadvertent casualties, it may undermine popular support for the resisters and instigate extreme repression.

In short, violence cannot be combined with nonviolence because the former negates the strengths of the latter.

But some radical critics disagree. Consider the position of what is termed “deep green resistance.” Deep green resisters are not opposed to nonviolent climate movements; rather, they believe that such movements alone will not succeed in saving the planet and its species. Saving the planet, for them, involves undermining the industrial civilization that is destroying the future of all life. What is needed, they contend, is full-spectrum resistance. The full spectrum includes clandestine organizations that are sometimes violent, in addition to the above-ground, and separate, nonviolent movements. The former, in aiming to dismantle existing power structures, may engage in violence not only against property, but also at times against persons (including the possibility of guerrilla warfare). To buttress their position, they claim that, in practice, most successful nonviolent movements have partly depended for their success on violence.

My own view is that clandestine groups employing violent means are less successful than nonviolent movements, morally suspect and conducive to authoritarian outcomes.

Nevertheless, deep-green resisters have a point. Violence and the threat of armed resistance may have played a larger role in effective civil disobedience campaigns than is usually acknowledged. Aric McBay in Full Spectrum Resistance reviews, among other cases, Gandhian resistance to the British in India and the civil-rights movement in the United States led by Martin Luther King. McBay contends that violence and threats of violence emanating from outside the nonviolent movements inclined governments to make concessions to the (more moderate) nonviolent organizations.

For example, the civil-rights movement in the United States in the 1960s won substantial concessions, largely in the form of federal legislation. Certainly, these concessions would not have happened without the courageous and skillful campaigns waged by MLK and his colleagues. In addition, however, the threat of violence hung in the air. McBay mentions the role of the armed Deacons for Defense in the US South, Malcolm X and the Black Muslims, inner-city riots and destruction, and, later, the threat posed by the Black Panthers. Concessions to moderates were not just the outcome of civil disobedience.

In a sense, this critique is not new. It is a version of the “left flank strategy” that has a long lineage. Simply put, the threat or actuality of violence by radical elements encourages the authorities to compromise with the more moderate nonviolent leadership.

How does this analysis of strategy relate to nonviolent resistance? Only this: to raise awareness that the injunction to maintain nonviolent discipline, though crucial, is not the whole story. Sabotage is permissible under certain circumstances. And the threat of guerrilla warfare, waged by a clandestine group, may also incline the usurpers/attackers to compromise with the nonviolent tendency.

Whether, of course, the civilian resistance should accept such compromises, is quite another story. In many cases, the civilian leadership should demur. It is often preferable to persist: to continue to vitiate the support base of the oppressors through nonviolent action, than to settle for mitigated domination.

Richard Sandbrook is professor emeritus of Political Science at the University of Toronto and President of Science for Peace.

“Non-violent defence” is an oxymoron. Or so it appears to many people. You hear the word “defence”, you think of “military”. You hear the term “national security”, you think of a state’s military strength (and perhaps diplomacy). The military has hi-jacked the terms defence and national security. Consequently, it sounds absurd to talk about non-violent defence.

But is the idea so preposterous?

Consider the war in Ukraine. Civilian resistance to the Russian invaders is inspirational. Civilians have blocked tanks and convoys, berated or cajoled Russian soldiers to undermine their resolve, given wrong directions to Russian convoys, refused to cooperate, and mounted spontaneous protests in occupied areas. And all these tactics were improvised on the spot.

Think how more effective non-violent defence would have been if it had been planned, and if Ukrainians had been trained in non-violent methods. With a civilian defence system in place, the Ukrainian armed forces might have allowed the Russian tanks to enter the country unimpeded. No immediate deaths, no destruction. And what can you, the invader, do with tanks when you face a population united in defiance, unarmed protest and complete non-cooperation? Ukraine would be indigestible.

Whether non-violent defence would have worked cannot be known. But what is certain is this: the prevailing notion of national security is leading us to death and destruction, in Ukraine and elsewhere. Thus, a potential alternative — civilian-based defence — deserves critical scrutiny. My earlier reflection on this system reviewed its strategy and tactics, some limiting conditions and provisos, and its potential benefits. Now I turn to lacuna and obstacles in the theory and practice of non-violent defence. Only hard-headed questioning will mitigate the skepticism surrounding this approach.

This critical review emphasizes the work of Gene Sharp – sometimes referred to as the “Clausewitz of non-violent warfare”. Recent major contributors on the methods of civilian resistance – in particular, Srdja Popovic and Erica Chenoworth – follow in Sharp’s footsteps. They provide either updated non-violent methods for a digital age (and for young rebels) or empirical evidence of the effectiveness of such an approach.

Two issues strike me as pivotal in getting real about non-violent defence. The first is recognizing and overcoming major domestic obstacles, especially vested interests, partisan divides, and apathy. The second involves seeing beyond the static typologies of non-violent action to conceptualize its implementation as a dynamic, mutually reinforcing process. Taking civilian defence seriously confronts its proponents with several dilemmas.

Non-violent defence is not simply a theory. Not only is there a long history of improvised civilian resistance to invasions, but also countries such as Sweden, Switzerland, Finland and Lithuania have institutionalized civilian defence at various times.

Consider Sweden: “Total defence” (military plus civilian defence) originated in neutral Sweden in the dangerous 1930s and World War II. Created in 1944, a Swedish Civil Defence Board undertook research on civil defence, organized training and oversaw the construction of air raid shelters. Sweden ran civilian-defence training centres in six cities during the Cold War. In 1986 the agency merged with the fire services board in a new Rescue Services Agency. The end of the Cold War led to a withering of the civil defence component. The initial idea – that all citizens had a duty to protect their country in an organized manner – fell into disuse by the mid 1990s.

The Russian attack on Georgia and seizure of Crimea however, revived the concept of total defence after 2014. Everyone between the age of 16 and 70 again has an obligation to respond in the event of an invasion or a natural catastrophe. “Everyone is obliged to contribute and everyone is needed” proclaimed a government pamphlet in 2018. Swedes were cautioned in the same pamphlet to prepare themselves for an emergency, though the emphasis was as much on peace-time natural emergencies as war. Nevertheless, in the event of war, the pamphlet declared that “we will never give up”. This basic idea is central to non-violent defence: an invader may occupy territory, but total non-cooperation and symbolic opposition will raise the costs of occupation, thereby discouraging invasion in the first place. In principle, all municipalities, voluntary organizations, businesses, trade unions, and religious organizations are required to prepare for civilian defence.

By March 2022, at the height of the war in Ukraine, one in three Swedes was fairly or very concerned their country would be attacked.. Furthermore, a 2021 survey registered popular support for the idea of civil defence: 84 percent of Swedes said they would be willing to play a defence role, so long as it was non-combative.

Sweden is not an ideal case of civilian defence. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the government talked of raising the defence budget and perhaps abandoning Sweden’s neutrality by joining NATO. But the idea of civil defence persists as a defiant complement, though not alternative, to military defence.

If a country were to experiment with non-violent defence, what obstacles would the experiment encounter?

Sharp in Chapter 5 of Civilian-Based Defense contends that non-violent defence, to succeed, must not only adhere to an all-of-society, nonpartisan approach, but also secure the cooperation of the armed forces. People of both sexes and all ages must participate, according to Sharp. They will do so out of patriotism, the desire to maintain their way of life, and an abhorrence of domestic and foreign usurpers alike. It will also be necessary to bring the military onside, claims Sharp. Civilian-based defence (CBD) may thus begin as a minor supplement to the armed forces, the former’s role expanding as it demonstrates its efficacy and popularity.

Is this a realistic scenario in today’s world? The establishment of CBD, from this viewpoint, is largely a top-down exercise, based on two assumptions. The first is that partisan cleavages are bridgeable. According to Sharp, civilian defence must be “transpartisan”. It must accommodate conservatives as well as liberals and socialists. If it becomes the project of a radical movement, or any single party, Sharp contends, its appeal will be too limited.

Secondly, this scenario assumes that reason will trump interests. The armed forces, various security apparatuses, suppliers of weapons and military technology and the national-security intellectual wing, are apparently swayed by evidence. Sharp emphasizes the importance of research in demonstrating CBD’s potential effectiveness. If research on CBD is positive, if the training of the population proceeds, and if civilians show enthusiasm, the armed wing of defence will acquiesce to the ascendancy of non-violent defence. Reason and patriotism will prevail.

Note that Sharp advocates “transarmament,” not disarmament. Presumably, it will be easier to sell CBD if it is seen not as pacifism, but as another form of struggle. The weapons in the new defence system are not munitions, missiles, warplanes, tanks; instead, they involve the subtle employment of 198 non-violent methods, their selection geared to the stage of engagement with the opponent, and the degree of the latter’s repressiveness.

I see three problems with this approach. The first pertains to interests. Sadly, we do not live in a world governed by reason; indeed, today people contest even what counts as fact. Interests shape dominant ideas, including those, or especially those, concerning national security. President Dwight Eisenhower, long ago, warned of the power of the military-industrial complex in bolstering military expenditures. Today, we would need to refer to an expanded military-industrial-security-intellectual complex. Thousands of billions of dollars are spent worldwide on the military and ancillary activities: on weapons, personnel, training, think-tanks, research and development. Many corporations, wealthy shareholders, employees and intellectuals are invested in perpetuating and extending the system of military defence. And defence budgets grow year after year.

In contrast, how much is spent on research on non-military forms of defence? Virtually nothing – perhaps the occasional grant for esoteric scholarly research.

Demilitarization will therefore involve a political struggle. It will be a struggle obviously in the superpowers. But even in in developing countries with weak institutions, the military tends to be comparatively strong. Much is at stake in defence policy for a range of powerful interests. No research results in favour of civilian defence are likely to persuade those whose profits, privileges or job depend on military defence. Non-violent defence – as more than a minor supplement to military defence – is a radical proposal.

Secondly, many societies today are riven with partisan divides and authoritarian tendencies. The United States is an obvious example, but the phenomenon is widespread, in Europe and beyond.

Is it possible to forge transpartisan support for CBD in these circumstances?

Sharp notes in Civilian-Based Defence (ch. 5) that non-violent defence is more likely to work where social cohesion is high and democracy and civil society are strong. However, these ideal conditions are not, he claims, prerequisites.

But is Sharp correct? Can non-violent defence happen in the absence of social cohesion and strong democracy? It seems unlikely. The issue would be politicized and viewed with deep suspicion by conservative/populist forces. And autocrats would not empower their people via training in nonviolence.

Thirdly, alienation and cynicism are rife in many societies today; Yet Sharp emphasizes that non-violent defence requires intensive preparation and training of all or most of a country’s population. What will induce people to shake off their apathy and devote their free time to training? Motivation is a problem, magnified by deep partisan divides.

All these considerations – vested interests, partisan divides and alienation – suggest that a top-down, apolitical approach will not work. The reality is that non–violent defence is a radical democratic initiative. Nonviolent action is inherently democratic to the extent that it empowers people vis-a-vis their rulers or aggressors. Only a mass movement will be powerful enough to overcome the vested interests in militarism and motivate people to participate in training and preparation.

Of course, even if CBD fails as a national system, or is limited to a subsidiary role, people may, when the need arises, spontaneously take up nonviolent resistance. But a trained response would be so much more effective.

The prospect of non-violent defence is enhanced if it is understood as a dynamic process, rather than a static design. Don’t get lost in Sharp’s 198 methods of non-violent action and the complexities of relating strategy to circumstances. The key is this: CBD focuses on agency. People possess power to shape their own futures; how therefore should this agency be harnessed for the common good? People have power because rulers depend on the ruled. Rulers cannot rule if the latter withhold their consent (or perhaps more accurately, assent). Thus, Sharp and his followers explore the bases of consent, and how consent can be denied to internal usurpers or external aggressors through nonviolent means.

Sharp and the others adhere to an inductive approach. They draw principles of effective action from successful and unsuccessful cases. In their examples, groups and individuals improvised responses to attempted domination — for example, the passive resistance of the German population to the French-Belgian occupation of the Ruhr Basin in 1923, the heroic non-violent resistance to German occupation in Denmark and Norway during World War II, and the astounding non-cooperation and defiance of the Czechs and Slovaks that met the Warsaw Pact army’s invasion to end the Prague Spring in 1968. The point of these cases is obvious: if improvised strategies can work so effectively, imagine if they were organized!

Fine. But how do you begin the process? Enthusiasm for nonviolent defence may be limited at first, and powerful groups will not cooperate and may be actively obstructive.

The process seems to work like this. The more the government builds the capabilities of the civilian defenders, the greater the willingness of people to unite and resist, drawing on the learned repertoire of nonviolent strategy and tactics. And the more advanced the capabilities and the united willingness of defenders to resist, the less likely that enemies will attack or usurpers will usurp power. The costs of domination become too high.

What comprise the capabilities of non-violent defence? They include organizational structure, committed and shrewd leadership, training facilities geared to the general population, the proportion of the population that wants to participate, and ultimately the strength of civil society.

The final factor alludes to the importance of institutional involvement in civilian-based defence. What political parties, trade unions, religious bodies, school systems, municipalities support the system? Obviously, nonviolent action is much easier to develop within a democracy; indeed, it is inherently democratic. Again, CBD empowers people.

As the capabilities grow, the willingness to resist and the participation of the population expands. Concomitantly, the costs of asserting domination on the part of usurpers or aggressors rises, enhancing the prospects of peace – provided the society in question is willing to pre-empt conflict by negotiating jointly acceptable solutions to outstanding disputes.

Demilitarization – reducing the budgets and roles of the armed forces – is a critical goal in today’s world. We face the rising probability of a nuclear holocaust resulting from accident, miscalculation, or escalation arising from a war like that in Ukraine. We are also very close to runaway global warming. The military, in the United States and increasingly elsewhere, is one of the largest institutional emitters of greenhouse gases. In addition, massive defence budgets are dedicated to waste – contributing neither to production not higher living standards – whereas we need to reallocate these resources to fighting climate change. Nonviolent defence, together with a renewed commitment to nuclear disarmament, is a potential way of achieving demilitarization.

Besides bolstering demilitarization, civilian defence has other positive outcomes. It reinforces civil society, builds democracy, discourages would-be tyrants and enemies, and extends norms of non-violent conflict resolution.

How then can we promote CBD? Civilian defence may proceed as a gradual process. Initially, it may be seen as only a supplement to military defence. Realism suggests that this approach is the most viable option. If popular enthusiasm grows and civilian capabilities advance, the military may be gradually reduced to a border control agency. But such a harmonious process is likely to be blocked at an early stage. Apolitical gradualism has severe limits.

Authoritarian states, for one thing, would balk at empowering their subjects. Civilian defence reveals the acute dependence of government on the assent of the ruled, together with the non-violent acts of omission and commission that withdraw that assent and paralyze rulership.

Nonetheless, in authoritarian systems, citizens have often improvised effective non-violent tactics. Consider the revolts of the people in eastern Europe and republics of the former Soviet Union in the late 1980s and early 1990s; the “Arab Spring” of the early 2010s, which featured in many cases massive street protests; the “colour revolutions” beginning in 2004 in the post-Soviet countries of Eurasia, including Ukraine; and the non-violent revolts against military rule in Sudan, Myanmar and elsewhere. Indeed, nonviolent protest reached its apogee in the period 2010-19, inhibited eventually by the pandemic.

Nonviolence, at a minimal level, is just common sense for people with grievances but without deadly weapons.

Partisan divides and power structures also hinder the expansion of nonviolent resistance at the expense of the military. “The people united will never be defeated,” yes. But the people are rarely united, and vested interests are powerful. Partisan and other cleavages allow those who govern to divide and rule their subjects. Social cohesion, together with democracy, is a key ingredient of success with non-violence. Unfortunately, many societies today are riven by partisan loyalties and authoritarian tendencies. What to do?

Accept the reality: civilian defence, in its full manifestation where the military’s role considerably shrinks, is a radical proposal. It will probably be advocated only by a progressive movement, along with measures to9 achieve democratization, equity, and a Green New Deal for a just transition. Civilian defence, as a radical project of democratization and demilitarization, is the missing link in the programs of the left.

What sort of states are the best candidates for CBD? Nuclear-armed states are unlikely candidates. From the strategic viewpoint, it is assumed nuclear weapons deter attacks. We know the logic is strong. How else could a nuclear power such as Russia, without the deterrent, get away with attacking and devastating Ukraine, the second largest country in Europe? States will be reluctant to surrender their nuclear weapons.

Non-violent defence can still play a supplementary role in the US, the UK, France, India and Israel, acting as a major deterrent to domestic usurpers of power and building civil society for the longer run. In addition, the more states adopting CBD, the lower the international threats; the lower the tensions, the more likely are agreements on limiting and eventually abolishing nuclear weapons. There is an indirect benefit of civilian defence.

Clearly, CBD would be easiest to introduce in small democratic countries and territories that lack a military. Cases that come to mind include Costa Rica, Mauritius and Iceland.

Countries bordering on a Great Power could also benefit from civilian defence. These countries could not hope to defeat an invading force from the superpower – or at least not without inflicting enormous damage and casualties upon themselves. Besides training the population in the principles and methods of nonviolent defence, civil society organizations would need to build strong links with peace groups internationally and with dissident groups within the superpower. The aim would be to precipitate internal dissent in the aggressor’s country and international condemnation of the invader, together with sanctions, in the event of a conflict. This strategy would proceed along with a willingness to negotiate to resolve conflicts with the great-power neighbour. Ukraine would have been a major candidate for such an approach. Smaller countries would be in a more dangerous position with CBD. They would face the prospect of forced assimilation to the dominant ethnic group of the superpower, as has happened in Tibet and the western regions of China.

Democratic middle powers, especially the Nordic countries, also offer an opportunity. Sweden is an exemplar. They would begin with civilian defence as a supplement to military defence. As CBD is a dynamic process, it might expand over a decade as it demonstrates its viability. Given catastrophic climate change, civilian and military defence would both expand to encompass preparation and training in handling “natural” disasters (extreme heat and storms, floods and forest fires). The body in charge might be termed a “civilian protection agency.”

Nonviolent defence is one element in a broader program to allow humans to live and thrive in an increasingly dangerous world. Politics is key.

Richard Sandbrook is professor emeritus of Political Science at the University of Toronto and President of Science for Peace.

Jim Morrison observed that nobody gets outta here alive. Though Morrison had a point, Kim Stanley Robinson sketches an optimistic scenario in which we – or many of us – do get out of the climate emergency alive. Robinson, in a book of 530 dense pages entitled The Ministry for the Future, mixes sci-fi with hard science to make his case. It is a tour de force, though a book of such demanding complexity that it is more likely to be talked about than read.

Despite the author’s touching belief in the sanctity of the rule of law, democratic representation and social and ecological justice, the book raises disturbing questions. Success in mastering climate change depends heavily on violence to deter carbon-intensive enterprises and life-styles and on extensive geo-engineering. Is this really what a just transition will entail? If so, how do those committed to non-violence and skeptical of geo-engineering respond?

Taken as a work of fiction, The Ministry for the Future is unconventional. Robinson blithely breaks all the rules of novel-writing. For one thing, very little character development takes place. For another, he stands the maxim, ‘show, don’t tell’ on its head. ”Tell, don’t show” prevails in the form of a series of mini-lectures ranging from the Jevons Paradox and cognitive behavioural therapy to the depredations of rentier capitalism and the promise of Modern Monetary Theory. So be warned: this is not a novel for leisurely reading.

Do enjoy the sheer audacity of the book’s shifting points of view, however. The novel shifts back and forth from third-person omniscient, for narrative and idea-development, to the first-person viewpoint of an amazing array: a photon from the sun, a reindeer, a carbon atom, Gaia, the weather system, and my favourite, the market. This zany approach entices the reader, but also makes us reflect on phenomena far outside our experience. This is, after all, only sci-fi.

Or is it? If it were sci-fi, we might dismiss it as a lark. We cannot dismiss this book, however, because it is heavily based on scientific knowledge and on existing climate trends. The mini-lectures are there not only to inform readers of complex realities, but also to persuade them not to dismiss the dangers he sketches as mere fiction. He harnesses the imaginative power of fiction to alert us to the imminent threat of climate disaster and to a potential pathway to safety and justice.

We begin the book with a searing portrayal of what lies just ahead. It describes in graphic detail a horrendous heat wave in central India that kills 20 million people. It is a horrifying event, yet the risk of such a deadly heat wave occurring in the next few years is high, according to climate scientists. As I was writing this article, NASA and NOAAA issued a report announcing that, in 2019, the earth trapped nearly twice as much heat than in 2005. Already, hundreds of thousands have perished from the heat throughout the world, including hundreds in France in 2003. Today, a headline caught my eye: ‘B.C. Records Hundreds of Deaths Linked to Heat Wave’. If a heat wave can hit Vancouver, where the weather is usually cool, no one is safe. Meanwhile, people in the Persian Gulf and the Indus Valley now regularly experience brief episodes of wet-bulb conditions beyond human endurance. We may know the facts, but Robinson’s fictional account brings home the terror.

So, what does Robinson propose? How do we get out alive?

We observe the climate crisis and the halting response to it mainly through the eyes of Mary Murphy, the thoughtful and committed head of the Ministry for the Future. Established under the Paris Climate Agreement, the Ministry is based in Zurich. Its mandate is exemplary: to work on behalf of children, those yet unborn and animals in pushing for measures to create a just and stable climate Predictably, the Ministry is poorly funded. Its international staff is over-stretched and ineffectual at first. But the ministry has a greater impact following a devastating global depression in the 2030s.

The survival scenario is too complex to summarize. Suffice it to say that there is no integrated program that rallies the world in concerted action. Instead, the world muddles through to the 2040s and 2050s. The concentration of carbon in the atmosphere begins to decline from a dangerously high 450 ppm, half of the world’s surface returns slowly to the wild, and the human population declines to a sustainable level. Robinson offers a decidedly democratic-socialist perspective, though his scenario involves no revolutionary upheaval. Instead, we witness a gradual movement to practical forms of cooperative organization and democratic representation. Strangely enough, the conservative central banks play a key role in this scenario. Mary and others persuade the bankers that, if we fail to conserve the world, worrying about inflation is pointless. Central bankers, tentatively at first, and then enthusiastically, embrace quantitative easing to support a new carbon coin currency, with one ton of sequestered carbon worth one coin. This stable currency persuades even petro-states and energy companies to accept complex compensation for leaving their hydro-carbon assets in the ground. All the parts of the puzzle fit together, though with many false starts.

Is all well that ends well? Not really. The scenario depends for its success on many strands, but two are controversial.

We may recoil at the geo-engineering, which is undertaken on a massive scale. The Indian government, following India’s devastating heat wave, resorts, without consulting other governments, to ‘solar radiation management’. It seeds the upper atmosphere with sulfur-dioxide dust to emulate the effect of a major volcanic eruption. The experiment reduces global temperatures marginally over three years. A second complex engineering feat, which I will not attempt to explain, is to stabilize glaciers in Antarctica. ‘This effort succeeds in slowing down the movement of glaciers into the sea, thus reducing the rise in ocean levels. Finally, the Russians dye the ice-free areas of the Arctic Ocean yellow to reflect solar radiation and impede oceanic warming. All experiments seem to have a positive effect.

The justification for geo-engineering is that global warming exceeds the point where it is reversible through conventional methods. Will this indeed be our predicament? Most of us harbour strong doubts about geo-engineering. We believe it is impossible, in complex systems, to gauge the unintended, and possibly devastating, effects of major interventions in climate dynamics. We may, however, be forced to rethink our position. Global warming is proceeding much faster than expected. Three or four degrees (Celsius) of warming would be disastrous. How many of us would survive as the tropical and semi-tropical regions become uninhabitable? If we are headed in that direction, we may have little choice but to consider geo-engineering as a last resort.

The second controversy concerns the legitimacy of employing violence to deter carbon-intensive activities and life-styles. In the novel, characters who have earned our respect condone the use of violence.

Attention in the novel focuses on a shadowy international ‘terrorist’ group based in India – the ‘Children of Kali’ – and a ‘black-ops’ group associated with the Ministry for the Future. Mary Murphy stumbles on the secret operations established by her deputy at the Ministry. She struggles with the morality of violence; Mary is depicted as a well-balanced, fair-minded democrat. Eventually, she accepts the necessity: ‘The hidden sheriff, she was ready for that now, that and the hidden prison. The guillotine for that matter. … The gun in the night, the drone from nowhere. Whatever it took. Lose, lose, lose, fuck-it – win!’

What transpires is a cascade of violence. Underground groups commit widespread sabotage of pipelines, polluting power stations, passenger jets (60 crash in a single day) and private passenger planes. Air travel ceases as dirigibles return. The Children of Kali assassinate billionaires who profit from hydro-carbons. Drones sink container ships and factory-fish ships, and pulverize cement factories, Cattle ranching ceases as a bovine fever fatal to humans spreads among cattle and other domestic animals. Direct attacks – such as an operation that kidnaps the rich and famous at an Economic Summit at Davos – strike fear into the hearts of the powerful. And the violence succeeds in lowering emissions. The age of carbon-intensive industry and travel ends, while vast tracks hitherto dedicated to animal agriculture revert to wilderness. As the human population dwindles, the natural world undergoes a renaissance. Consequently, the concentration of carbon dioxide begins a steady decline in the 2040s or 2050s.

Considering the beneficial outcomes, is violence justified in the fight for a just transition?

Those of us committed to non-violence would answer in the negative. Yet, whether we like it or not, violence is likely to come. As extreme weather events multiply, as these events destroy agricultural and other livelihoods, the resulting panic and anger create conditions for extremism and ‘terrorism.’ In fact, adverse climatic trends are already exacerbating violent conflicts in tropical regions; in Syria, Sudan, Mali, and Central America, for instance. Security agencies in the United Kingdom and Canada have already identified such non-violent groups as Extinction Rebellion, Greenpeace, and PETA as potentially subversive. Extreme climate, loss of livelihoods, growing criminality, and collapsing governments are fuelllng a growing stream of climate migrants/refugees. If we do not take decisive action to halt carbon emissions, with dangerous tipping points in the offing, we invite instability, conflict and violence.

Combating global warming is thus not just a fight for climate activists; it is a fight for peace and justice activists as well. Kim Stanley Robinson shows as what might happen. But we have agency, and the violence and chaos that might happen, must not happen. Robinson’s final words are not exactly a consolation, but at least ground us in the reality of our situation: “We will keep going, we will keep going because there is no such thing as fate. Because we never really come to the end.”

New York Times technology reporter Kevin Roose begins his new book with some good news.

Futureproof: Nine Rules for Humans in the Age of Automation, (2021) adopts an upbeat tone in proposing how we might live well in this age of automation. “Artificial intelligence could be unbelievably good for humankind, if we do it right. A world filled with AI could also be filled with human creativity, meaningful work and strong communities.” Furthermore, artificial intelligence and automation “could bring us together, armed with new superpowers, to solve some of our biggest problems.” What problems? Big, big ones: to “eliminate poverty, cure diseases, solve climate change, and fight systemic racism.” Great!

But his repeated use of the conditional verb “could” evokes caution. Is this vision only hypothetical?

It appears to be so: Roose notes that “none of this will happen without us.” Well, that’s not a surprise. What do “we” need to do?

Therein lies the rub. Roose offers no plan because he lacks a problematic. Yes, he is rightfully skeptical “that the private sector will save us.” Yes, he thinks a strong welfare state and extensive retraining programs are needed to handle the disruptions. Yes, he implores us to stop bowling alone and recreate community in order to back “collective action.” But how do we overcome atomization, and for what sort of joint action? No answer, except for a stirring call to “arm the rebels” within the high-tech oligopolies – the usual suspects: Amazon, Google, Apple, Facebook, Alibaba, Microsoft, and others. Well, that’s something of a political nature.

But very thin gruel. Roose’s idea of arming tech rebels fighting for “ethics and transparency” is to provide them with “tools, data and emotional support.” That doesn’t sound promising, though further revelations of algorithmic manipulations and the unsavoury military contracts of big tech are important.

Not surprisingly, with little to offer, Roose concludes by urging his readers not to get “too discouraged.” If “we” are determined, “we” may still harness technology for the common good.

Am I too harsh in my judgment? You judge. Roose’s approach is emblematic of what we might term a “progressive neoliberal” stance. That stance deplores certain social trends, hopes for good social and ecological outcomes, but it hasn’t a clue how to bring them about. The failure stems from avoiding an analysis of systemic power relations, of which technological development is one pillar. The analyst turns instead to the easier question of how individuals can best accommodate existing trends. The author’s “Nine Rules for Humans in the Age of Automation” enumerate common-sensical ways in which humans can individually adapt to, and perhaps even thrive with, this runaway monster. Believing that another glorious world is possible leads nowhere if you lack a strategy.

But you may ask: is there really a problem with AI that requires a problematic? Can’t we just keep clicking happily away on our phones while hoping for the best? After all, learned economists claim that, in the long run, everyone benefits from automation because more and better jobs are created than are lost. Overall, living standards and satisfactions allegedly rise. Let’s click and be happy!

Sorry, no. The techno-optimists’ view is suspect. Although saying a good word on behalf of the machine-wrecking Luddites is considered a mark of intellectual ineptitude, we may at least understand their anger. The following questions just touch the surface of what is at issue:

Yes, there is a problem with AI. We live in a world faced with destruction from new generations of nuclear weapons, hatred spawned by the manipulated identities of those left behind by technological and social change, and accelerating global warming. All these problems grow worse as companies devote billions of dollars, thousands of PhDs, and millions of hours to perfecting algorithms to control our shopping and political preferences. From a societal viewpoint, it’s mad.

Thus, we return to the issue of a problematic. Lacking a problematic is a debilitating weakness when it comes to harnessing technological development. If you don’t understand the dynamics, you can’t think through feasible means of taming the beast.

So what is the problematic? It is devastatingly simple. I learned this truth years ago when I taught the political economy of technological change. Technological development is not a force of nature; it does not just happen. There are many innovations and inventions that could be harnessed. Those that come to fruition – receive finance and nurture – are the ones that suit the economic and power interests of the dominant elites. This self-evident truth increasingly applies to university-based research as well as commercial research. The incentives make it so.

Strategically, the implication is that if you want to change the pattern of technological development, you have to challenge the power structure. Roose is right: artificial intelligence could be “unbelievably good for humankind.” With enhanced productivity and new ways of interacting, we could solve our major problems and extend the realm of freedom for all. But not by following Roose’s nine rules of individual adaptation. Yes, “none of this will happen without us.” Yet that admonition requires substance.

Can “we” take on power structures? Can we organize a progressive mass movement that avoids the usual problems of sectarianism, identity clashes and schism? Can we develop a program that might have wide appeal, despite the rise of populist-nativism? It is a daunting challenge, especially in this age of surveillance capitalism powered by AI. But we have no other option but to try – if we want to be “futureproof.”

[header image: Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay]

This is the decisive decade for humankind and other species. We tackle dire trends now. Or we face a bleak future in which our constricted pandemic life now becomes the norm for all but the wealthiest. Our rational and technological prowess, in combination with market-based power structures, has brought us to the brink of catastrophe. Can movement politics be part of a solution?